The

Mixup in a Wife about Coldness & Warmth

By Anne Fielding

Here is a wife speaking to her husband in an

Irish play of 1926:

I’m longin’ to show

you me new hat, to see what you think of it. Would you like to

see it? [A knock is heard at

the door.]

Take no notice of it,

Jack. Don’t break our happiness. Pretend we’re not in. Let

us forget everything tonight but our own two selves. Please,

Jack, don’t open it. Please, for your own little Nora’s sake!

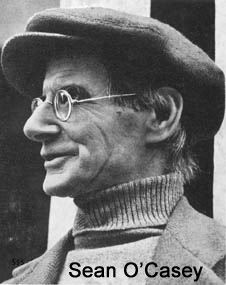

This is Nora Clitheroe in Sean O’Casey’s The Plough & the Stars, a wife

very much in a mixup about warmth and coldness.

In a lecture Eli

Siegel, the founder of

Aesthetic Realism, gave on the subject of imagination, he noted that

Nora is a woman who wants the close presence of the man who said

he loved her. In this scene, she’s intense, heated, but what is

she warm about—having her husband praise her new hat, and keeping other

people out.

Warmth, to Nora, means having this man exclusively hers, devoted,

protecting her from a world and people she sees as cold and mean.

She’s against his passionate desire to fight for Irish freedom,

insisting he stay home and pay homage to her.

Nora’s situation is

dramatic, but she’s very representative, because many a wife—not in a

play, but in real life—has felt marriage was a time to “forget

everything but our own two selves,” been angry at her husband’s

interests outside the home, and not understood why there came to be

such painful coldness and anger between them.

In an issue of the journal The Right

of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, Ellen Reiss, the Chairman

of

Education, has sentences that show what’s at the heart of this mixup:

Coolness

and warmth

are ethical opposites. What we are warm to and what we are cool to

determine how just a person we are. Aesthetic Realism shows that our

purpose in being close to a person should be to like the world

itself. And if two people are “warm” to each other for the purpose of

getting away from the world and of making themselves superior to the

world, they will feel profoundly betrayed by each other. And

there will come to be a deep anger and coldness between them.

This is what Mrs. Darcy Banks had

experienced,

as she told us in an Aesthetic Realism consultation. Her husband

Thomas, she said, was often irritated with her, and, she said, “My

marriage is a hotbed of disappointment and resentment—I need to

understand why.”

I Learned the Mixup

Begins Long Before Marriage

Like many young girls, I was very

much

concerned with how “warm” people

were to me, and judged them accordingly. Did they smile when I came

into the room, praise my piano playing, tell my mother how talented I

was? I disliked it very much when anyone had the nerve, as I saw

it, to offer some criticism of me—and was particularly enraged and

tearful at any suggestion that I was “spoiled.” In The Right Of,

Ellen Reiss asks this question which I needed so much to hear:

Do you tend to see

criticism of you as cold and praise of you as warm?

This is one of the stupidest mistakes people make.

I made this mistake

early—particularly in how I saw my father. I

resembled him in looks and he made a lot of me, doted on and coddled

me; relatives referred to me as “Daddy’s girl.” I discovered early how

to wheedle my way, and remember my sister telling me angrily, “You’ll

get anything you want from him,” which made me wince because it was

so. Inside I was uncomfortable and ashamed because I knew I

didn’t deserve such devotion, and I thought my father was foolish in

giving it, but continued to angle for it, eat it up, thinking this was

warmth, while most other people were severe and cold, making my life

miserable.

That is what Nora Clitheroe, in The Plough and the Stars feels as

she says: “What do I care for the

others? They have

dhriven away th’ little happiness life had to spare for me.”

How big is this in a person—the

feeling that the world and people are

cruelly cold to one? It’s huge and it’s terrifically

attractive. And it’s Aesthetic Realism that explains for the

first time that as this wife says so seemingly pathetically, “They have

dhriven away th’ little happiness life had to spare for me,” not only

is she wrong—the O’Casey play shows that, but she’s having a tremendous

victory of contempt, warm to herself while coldly superior to the rest

of the world—and she doesn’t know she’s ruining any chance for real

happiness and love.

By the time I was in my teens I

had come to associate love with a man

being fervent and intense about me, calling me frequently, etc. On a

date, I prided myself in being able to speak eloquently, but inwardly

felt stony and strategic, like I was putting on a show. Meantime,

I had a big desire to act and to have large feeling in a role, but I

couldn’t; and in scenes I did in acting classes, I was often very stiff

and cold inside. I needed so much to know what Ellen Reiss write in her

commentary, that:

If there

is something unjust and hurtful in us, criticizing us so we be

better is tenderness, is tremendous, kind warmth.

It was my great good fortune, a

few years later, to receive this

tremendous kindness from Eli Siegel in Aesthetic Realism lessons and

classes—and I thank him. He criticized a way of seeing that was

holding up my life in two big fields—love and acting, and taught me, to

my great benefit, that the purpose of both is exactly the same: to know

and like reality itself, through knowing deeply a particular person—a

man, or a character in a play.

In one Aesthetic Realism lesson,

when I said I’d gotten angry with a

man I was dating because he didn’t appreciate my good qualities and was

much too severe, Mr. Siegel asked me: “Is your desire for approval

inordinate?” When I said I thought so, he asked, “What’s wrong

with it?” and then explained:

The

trouble with the instinct for approval is that it’s in conflict

with another instinct—the instinct for criticism. Having a man’s

approval can’t be disassociated from having him dance on the end of a

string. Your problem is the problem of Woman. Don’t give it a false

uniqueness. Like other women you want

approval and pampering, but you have contempt for the person who gives

it to you, and you are angry with yourself for taking it.

Mr. Siegel was right. And I’ve

seen that when a woman tries to have a

man dance on the end of a string—like a puppeteer—she’s coldly

manipulating him in behalf of her ego, and it’s not love at all: it’s

ill will and contempt, the very thing that ruins love.

I began to

see that I wanted something much better, and as my study continued, I

met, fell in love with, and married Sheldon Kranz, Aesthetic Realism

consultant and poet. Here was this learned, attractive man who

didn’t lavish me with praise; but who showed deep care for me in

encouraging my study of drama and literature, whose heartiness and

humor usefully countered my tendency to melodramatic gloom, and who

even gave me astute criticism on how my acting could be better.

And through what we both learned

in classes taught by Mr. Siegel, some

years later I had the honor to become an Aesthetic Realism consultant and to teach this knowledge to other women.

One of these women is Darcy

Banks, living in upstate New York,

whose husband, Thomas, teaches agriculture in a community

college. “How can I understand my husband?” she asked There Are Wives. “He’s been cold and petulant, telling me I was selfish and

felt I owned him.”

Our

Hopes Need Criticism

In The Right Of, Ellen Reiss explains:

In

our desire for contempt, we hope the world is cold, because a cold

world is a world to which we, in our sensitivity, can feel superior. If

things are truly warm to us, we will have to feel grateful to them!

When Mrs. Banks began

having

consultations with There Are Wives, we saw

a very pretty woman who cared for science, animals, and nature, and

worried about the increasing coldness and anger in her marriage. As she

spoke, there was a certain laid-back coolness in her manner, with a

tendency towards sarcasm.

Is sarcasm cold or hot

or some bad

combination of both? A woman can be in a rage and make an icily cutting

remark for the purpose of swift contempt.

Meanwhile, we

respected very

much Mrs. Banks’ large desire to criticize herself, and to be sincerely

warmer.

When we asked what she

would most like to change in

herself, Mrs. Banks

replied: “Ways I find myself fighting with the world.” This took in,

she said, fighting with co-workers, with friends whom she felt had hurt

her, and very much her husband.

She told us he often

needed to

stay late at school, and that she’d come

home from her job as office manager very tired, and feel, “I just want

to be taken care of.” On weekends, her husband spent many hours working

in a cooperative orchard nearby, and though he’d ask her to assist him

there, she’d often refuse. Many wives have been cold to their husbands'

interest in things other then themselves.

In the O’Casey play, when

Jack Clitheroe says to his wife: “it’s sure to be a great meetin’

tonight. We ought to go, Nora,” she replies with a kind of sulky

coolness, “I won’t go, Jack: you can go if you wish.” A woman often

punishes her husband showing she’s hurt when he dares to care for

something not her.

Mrs. Banks had done this. She told

us, “I’ve wanted Tom to be happy in

the country, meeting new people in the town. At other times I catch

myself with a feeling of resentment that he’s so carefree. He doesn’t

have a care in the world. The result of this feeling is that I’m alone,

cold, angry and disappointed.”

To say her husband

didn’t have a

care in the world was untrue and also

cold. He had many cares—including about his intense teaching schedule,

worries about money and the future, and about health. And he also was

very much concerned about what was happening in America and the world,

including what people were enduring economically. When he was

courting her, Darcy Banks was interested in his thoughts about things,

but now, she often got to what she described as “an icy anger with

him.”

They argued, as couples do, about everyday

things—about lists for

food shopping, about preparing meals, about taking care of their

animals, and she had, she said, “much less feeling for him.” When

we told her that Eli Siegel once explained: everybody has an awful

fight between being cold and having feeling, she saw that she was not

in unique, sad isolation. And she learned about this question:

Do

I Use My Husband to Be Warm or Cold to Others?

A big aspect of a

wife’s mixup

about these opposites is in whether she

uses her husband as a means of seeing other people as for her, or uses

him as a protection agency, defending her from what she sees as

the coldness and meanness of others. In a class, Mr. Siegel once

asked me and Sheldon, did we want to use each other as collaborators,

or as creative encouragement? And in The

Right Of, Ellen Reiss

asks this question, which Mrs. Banks saw was crucial for her:

Have you divided

reality into that part of it to which you will be

“warm” (your family, some friends, certain fields of interest), and a

huge rest-of-the-world to which you are deeply cold?

In the O’Casey play, when a

neighbor, Bessie Burgess, suggests that

Nora Clitheroe is cold to people, “Always’ thryin to speak proud

things, and lookin’ like a mighty one,” Nora’s husband make a fatal

mistake, collaborates with the worst thing in his wife, saying to Mrs.

Burgess:

Get up to your

own

place, Mrs. Burgess, and don’t you be interferin’

with my wife, or it’ll be worse for you. There, don’t mind that

old bitch, Nora, darling; I’ll soon put a stop to her interferin’.

And Nora smugly laps it up. Later

in the play, she’ll say to him, “I

want you to be thrue to me, Jack. I’m your dearest comrade; I’m your

dearest comrade,” which is a lie, and he knows it, becoming

increasingly enraged and humiliated by her intense drive to keep him to

herself at the cost of the work he’s given his life to—fighting for the

freedom of Ireland. And Nora smugly laps it up. Later

in the play, she’ll say to him, “I

want you to be thrue to me, Jack. I’m your dearest comrade; I’m your

dearest comrade,” which is a lie, and he knows it, becoming

increasingly enraged and humiliated by her intense drive to keep him to

herself at the cost of the work he’s given his life to—fighting for the

freedom of Ireland.

Mr. Siegel once asked

me: “What is

more

important to you—to have Sheldon honor you or be true to himself.” The

first is ill will, the second is good will. With all her fervency and

warmth for him, Nora doesn’t have good will for her husband, and she

will suffer greatly as the play proceeds.

In The Right Of, Ellen Reiss

describes magnificently the thing

that solves the mixup in a wife between coldness and warmth:

Good will is the

oneness of heat and cold; for when you have good will,

you passionately want a person to be all he or she can be, and you are

passionately against what is not beautiful in the person. Good

will is the great, eternal coolness of accuracy and the warmth of deep

feeling.

That is what, as dramatist, the

playwright Sean O’Casey shows as he

gives form—with imaginative justice, “coolness of accuracy and warmth

of deep feeling,” to the intimate lives of women and men of Ireland in

their cheapness and nobility, their coldness and warmth, during one of

the most important times in that country’s history. And that is why his

play stirs us powerfully and can educate us usefully.

As Darcy Banks

consultations

continued, she also attended the monthly

Understanding Marriage class where she saw herself in relation to other

women, and she became increasingly kinder and happier. Thomas Banks

respected the changes in his wife and got more hope for his life

and their marriage. He began to study Aesthetic Realism for himself.

An assignment we gave Mrs. Banks was: Write ways

you’re proud to need

your husband. Here are three:

1. I need

Thomas Banks to be in a better relation to other

people, and to make friends. He draws people out,and he’s not shy

about asking people questions. I need this aspect of him because I see

people have more friendliness than I had thought previously.

2. I need my

husband’s unique way of seeing the world to be a

well-rounded person, which I want to be. He knows a lot of history and

geography and I feel a sense of pleasure when he tells me what he’s

reading. He’s had me see men more deeply, and shown me if you care for

something it is because of what that thing is, not because it approves

of you.

3. Sometimes I

get into a funk, and I need Tom because he derails

the contempt train which makes me feel so miserable. He has many

approaches to my bad moods—often with warm, surprising humor. He

represents the world, frequently shining a light into my depths. His

questions and presence have a good effect on me, which I’m seeing I

need every day, and I’m grateful.

Mrs. Banks stands for

what wives

everywhere are hoping to know.

|